The happy idea of using a proletarian holiday celebration as a means to attain the eight-hour day was first born in Australia. The workers there decided in 1856 to organize a day of complete stoppage together with meetings and entertainment as a demonstration in favor of the eight-hour day. The day of this celebration was to be April 21. At first, the Australian workers intended this only for the year 1856. But this first celebration had such a strong effect on the proletarian masses of Australia, enlivening them and leading to new agitation, that it was decided to repeat the celebration every year...Thus, the idea of a proletarian celebration was quickly accepted and, from Australia, began to spread to other countries until finally, it had conquered the whole proletarian world...The first to follow the example of the Australian workers were the Americans. —Rasa Luxemburg

The first of May was originally celebrated by pagans throughout Europe as the beginning of summer, which was recognized as a day of fertility (both for the first spring planting and sexual intercourse). A maypole was often erected for young women and men to dance around and entwine the ribbons they carried with one another to find a mate... at least for the night. Persecution of May Day began as early as the 1600s; in 1644 the British Parliament banned its practice as immoral, with the Church bringing its full force to bear across the spectrum. Governments throughout Europe were largely ineffective in outlawing these celebrations, and thus the Church took a different approach – it attempted to assimilate the festivities by naming Saints days on the first of May. These efforts led to the destruction of May Day in some places, but the traditions and customs of May Day continued to remain strong throughout much of the peasantry of Europe, whose ties to one another and nature were far stronger than their ties to the ruling class and its religion. Celebrations became increasingly festive, especially at night when huge feasts, songs, dance, and free love were practiced throughout the night.

•After the birth of capitalism, the roots, and principles of the tradition survived to various extents, with workers across Europe celebrating the first of May as the coming of spring and a day of sexual

fertility. Most mythical and religious sentiments faded away, but the spirit of the festival in expressing the love of nature and one another gained strength.

• At the end of the eighteenth century, May 1 became popular as International Workers’ Day throughout the world mainly to working people and a symbolic day of emancipation from the slavery of capitalism.

•International Workers’ Day (also known as May Day) is a celebration of the international labor movement. May 1 is a national holiday in many countries today and celebrated unofficially in many other countries.

•It is the commemoration of the 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago, a small industrial city belong to Illinois state of the USA. The Haymarket affair was the aftermath of a bombing by an unidentified person that took place at a labor demonstration on Tuesday, May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in Chicago. The demonstration began as a peaceful rally in support of workers striking for an eight-hour day and in reaction to the killing of several workers the previous day by the police. The aftermath of bombing was bloodshed, the police reacted by firing on the workers, killing dozens of demonstrators and several of their own officers.

•In October 1884, a convention held by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (which later became the American Federation of Labor) unanimously set May 1, 1886, as the date by which the 8-hour workday would become standard. As the chosen date approached, U.S. labor unions prepared for a general strike in support of the eight-hour day.

•In 1885 a circular passed hand to hand through the ranks of the proletariat in the United States. With the following words, it called for class-wide action on May 1, 1886: “One day of revolt – not rest! A day not ordained by the bragging spokesmen of institutions holding the world of labor in bondage. A day on which labor makes its own laws and has the power to execute them! All without the consent or approval of those who oppress and rule. A day on which in tremendous force the unity of the army of toilers is arrayed against the powers that today hold sway over the destinies of the people of all nations. A day of protest against oppression and tyranny, against ignorance and war of any kind. A day on which to begin to enjoy ‘eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.’”

•On Saturday, May 1, 1886, thousands of workers went on strike, and rallies were held throughout the United States, with the cry, “Eight-hour day with no cut in pay”. Estimates of the number of striking workers across the U.S. ranged from 300,000 to half a million. In New York City the number of demonstrators was estimated at 10,000 and in Detroit at 11,000. In Chicago, the movement’s center, an estimated 30,000-to-40,000 workers had gone on strike and there were perhaps twice as many people out on the streets participating in various demonstrations and marches.

•On May 3, striking workers in Chicago met near the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company plant. Union molders at the plant had been locked out since early February and the predominantly Irish-American workers at McCormick had come under attack from Pinkerton guards (Private forces employed by industrialists, especially during the second industrial revolution, to break up, often very forcibly, riots and protests against the terrible living and working conditions, etc) during earlier strike action in 1885. This event, along with the eight-hour militancy of McCormick workers, had gained the strikers some respect and notoriety around the city. By the time of the 1886 general strike, strike-breakers entering the McCormick plant were under protection from a garrison of 400 police officers. Although half of the replacement workers defected to the general strike on May 1, McCormick workers continued to harass strike-breakers as they crossed the picket lines.

•Speaking to a rally outside the plant on May 3, August Spies advised the striking workers to “hold together, to stand by their union, or they would not succeed.” Well-planned and coordinated, the general strike to this point had remained largely nonviolent. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, however, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the strike-breakers. Despite calls for calm by Spies, the police fired on the crowd. Two McCormick workers were killed (although some newspaper accounts said there were six fatalities).

•Outraged by this act of police violence, a section of labor organizers (suspected to be the local members of an anarchist organization called ‘International Working Peoples’ Association’) gathered in a meeting at Grief’s Hall that night and decided to hold a protest the following evening near Haymarket Square (also called the Haymarket), which was then a bustling commercial center near the corner of Randolph Street and Desplaines Street. The next morning, one of those anarchists, Adolph Fischer, arranged with August Spies, manager of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, to publish fliers calling for a rally the following day at Haymarket Square. Printed in German and English, the fliers claimed that the police had murdered the strikers on behalf of business interests and urged workers to seek justice. The first batch of fliers contain the words Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force! Spies was also invited to speak at the meeting and initially, he agreed, but when he saw the inflammatory phrase (“Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force”) he said he would not speak at the rally unless the words were removed from the flier. Nevertheless, copies of the original flier were already distributed and a few hundred of the fliers were destroyed, and new fliers were printed without the offending words. More than 20,000 copies of the revised flier were distributed.

•Two or three thousand people gathered at Haymarket Square on the evening of May 4, but the crowd was smaller than hoped. The rally began peacefully under a light rain. August Spies, Albert Parsons (the suspected anarchist), and Samuel Fielden spoke to a crowd estimated variously between 600 and

3,000 while standing in an open wagon adjacent to the square on Des Plaines Street. A large number of on-duty police officers watched from nearby. The object of this meeting was to explain the general situation of the eight-hour movement and to throw light upon various incidents in connection with it.

•Following Spies’ speech, the crowd was addressed by Parsons, the Alabama-born editor of the radical English-language weekly The Alarm. Parsons spoke for almost an hour. The last speaker of the evening, the British socialist Samuel Fielden, delivered a brief ten-minute address. Many of the crowd had already left as the weather was deteriorating.

•At about 10:30 pm, just as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived en masse, marched towards the speakers’ wagon, and ordered the rally to disperse. Fielden insisted that the meeting was peaceful. But police Inspector John Bonfield proclaimed: I command you (addressing the speaker) in the name of the law to desist and you (addressing the crowd) to disperse. In his testimony before the court about three months later, Fielden recalled: “I do not think I should have spoken one minute longer when I noticed the police. I stopped speaking and Captain Ward came up to me, and he raised his hand —, and I do not remember now whether he had anything in his hand or not —; and he said: ‘I command this meeting, in the name of the People of the State of Illinois, to peaceable disperse.’ I was standing up, and I said ‘Why Captain, this is a peaceable meeting,’ in that tone of voice, in a very conciliatory tone of voice, and he very angrily and defiantly retorted that he commanded it to disperse, and called, as I understood — I didn’t catch those words clearly — he called up the police to disperse it. Just as he turned around in that angry mood I jumped from the wagon and said ‘All right, we will go,’ and jumped to the sidewalk. . . . Then the explosion came.”

•At this time suddenly a home-made bomb, which was thrown into the path of the advancing police, exploded killing policeman Mathias J. Degan and wounding six other officers. Immediately after the bomb blast, as reported, there was an exchange of gunshots between police and demonstrators, but it is very difficult to say what really happened Accounts vary widely as to who fired first and whether any of the demonstrators fired at the police at all. What is not disputed is that in less than five minutes the square was empty except for the casualties. The Chicago Herald (May 5, 1886) described a scene of “wild carnage” and estimated at least fifty dead or wounded civilians lay in the streets.

•In all, seven policemen and at least four workers were killed that day. Another policeman died two years after the incident from complications related to injuries received on that day. About 60 policemen and a large number of workers were wounded in the incident. It is unclear how many workers were wounded since many were afraid to seek medical attention, fearing arrest. They found aid where they could. A very large number of the police were wounded by each other’s revolvers.

•The writer of the Special Presentation, The Dramas of Haymarket, Professor Carl Smith, concludes: “The state’s witnesses maintained that the bombing was instantly succeeded (some said preceded) by gunfire from the crowd, and that the police valiantly held their position and returned fire. But the weight of the testimony and evidence suggests that understandably terrified by the blast, the policemen initiated the gunplay, firing every which way, including into their own ranks. While several of their number besides Degan appear to have been injured by the bomb, most of the casualties seem to have been caused by bullets. About sixty officers were wounded in the riot, as well as an unknown number of civilians. Among the latter were Samuel Fielden and August Spies’ brother Henry, who were both hit by gunfire but managed to get away. . . .Others tried to escape as quickly as they could, scattering in all directions as the police used their pistols and clubs indiscriminately.”

•A harsh anti-union clampdown followed the Haymarket incident. The entire labor and immigrant community, particularly Germans and Bohemians, came under suspicion. Scores of suspects, many only remotely related to the Haymarket affair, were arrested. Casting legal requirements such as search warrants aside, Chicago police squads subjected the labor activists of Chicago to an eight-week shakedown, ransacking their meeting halls and places of business. The emphasis was on the speakers at the Haymarket rally and the newspaper, Arbeiter-Zeitung.

•Police raids were also carried out on homes and offices of suspected anarchists. A small group of anarchists was discovered to have been engaged in making bombs on the same day as the incident, including round ones like the one used in Haymarket Square. The police assumed that an anarchist had thrown the bomb as part of a planned conspiracy; their problem was how to prove it.

•Among property owners, the press, and other elements of society, a consensus developed that suppression of anarchist agitation was necessary. While for their part, union organizations such as The Knights of Labor and craft unions were quick to disassociate themselves from the anarchist movement and to repudiate violent tactics as self-defeating. Many workers, on the other hand, believed that men of the Pinkerton guards were responsible because of their tactic of secretly infiltrating labor groups and its sometimes violent methods of strike breaking.

•While state terror was going on to suppress workers, there was a massive outpouring of community and business support for the police, and many thousands of dollars were donated to funds for their medical care and to assist their efforts.

•On the morning of May 5, they raided the offices of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, arresting its editor August Spies, and his brother (who was not charged). Also arrested were editorial assistant Michael Schwab and Adolph Fischer, a typesetter. A search of the premises resulted in the discovery of the “Revenge Poster” and other evidence considered incriminating by the prosecution.

•On May 7 police searched the premises of Louis Lingg where they found a number of bombs and bomb-making materials. Lingg’s landlord William Seliger was also arrested but cooperated with police and identified 21 years Lingg as a bomb maker and was not charged. An associate of Spies, Balthazar Rau, suspected as the bomber, was traced to Omaha and brought back to Chicago. After interrogation, Rau offered to cooperate with the police. He alleged that the defendants had experimented with dynamite bombs and accused them of having published what he said was a code word, “Ruhe” (“peace”), in the Arbeiter-Zeitung as a call to arms at Haymarket Square.

•By May 14, when it became apparent that Rudolf Schnaubelt, the police’s lead suspect as the bomb thrower, who was arrested twice early but released, had played a significant role in the event, he had fled the country. William Seliger, who had turned state’s evidence and testified for the prosecution, was not charged.

•On June 4 of the same year, seven other suspects, however, were indicted by the grand jury and stood trial for being accessories to the murder of Degan. Of these, only two had been present when the bomb exploded. Newspaper editor August Spies and Samuel Fielden had spoken at the peaceful rally and were stepping down from the speaker’s wagon in compliance with police orders to disperse just before the bomb went off. Two others had been present at the beginning of the rally but had left and been at Zepf’s Hall, an anarchist rendezvous, at the time of the explosion. They were: Arbeiter-Zeitung typesetter Adolph Fischer and the well-known activist Albert Parsons. Parsons, who believed that the evidence against them all was weak, subsequently voluntarily turned himself in, in solidarity with the accused. A third man, Spies’s assistant editor Michael Schwab was arrested since he was speaking at another rally at the time of the bombing (he was also later pardoned). Not directly tied to the Haymarket rally, but arrested because they were notorious for their militant radicalism were George Engel (who was at home playing cards on that day), and Louis Lingg, the hot-headed bomb maker denounced by his associate, Seliger. Another defendant who had not been present that day was Oscar Neebe, an American-born citizen of German descent who was associated with the Arbeiter-Zeitung and had attempted to revive it in the aftermath of the Haymarket incident.

•Of the eight defendants, Spies, Fischer, Engel, Lingg, and Schwab were German-born immigrants; a sixth, Neebe, was a U.S.-born citizen of German descent. Only the remaining two, Parsons and Fielden, born in the U.S. and England, respectively, were of British heritage

•The trial, Illinois vs. August Spies et al., began on June 21, 1886, and went on until August 11 of the same year. The trial, which is now considered one of the worst miscarriages of justice in American history, was conducted in an atmosphere of extreme prejudice by both public and media toward the defendants. It was presided over by partisan Judge Joseph E. Gary who displayed open hostility to the defendants, consistently ruled for the prosecution, and failed to maintain decorum. All 12 jurors acknowledged prejudice against the defendants.

•Selection of the jury was extraordinarily difficult, lasting three weeks, and nearly one thousand people called. All union members and anyone who expressed sympathy toward socialism were dismissed. Frustrated by the hundreds of jurors who were being dismissed, a bailiff was appointed who selected jurors rather than calling them at random. The bailiff proved prejudiced himself and selected jurors who seemed likely to convict based on their social position and attitudes toward the defendants.

•The defense counsel included Sigmund Zeisler, William Perkins Black, William Foster, and Moses Salomon. A motion by the defense to try the defendants separately was denied. The prosecution, led by Julius Grinnell, argued that since the defendants had not actively discouraged the person who had thrown the bomb, they were therefore equally responsible as conspirators. The jury heard the testimony of 118 people, including 54 members of the Chicago Police Department and the defendants Fielden, Schwab, Spies, and Parsons. Albert Parsons’ brother claimed there was evidence linking the Pinkertons to the bomb. This reflected a widespread belief among the strikers.

•Police investigators under Captain Michael Schaack had a lead fragment removed from a policeman’s wounds chemically analyzed. They reported that the lead used in the casing matched the casings of bombs found in Lingg’s home. A metal nut and fragments of the casing taken from the wound also roughly matched bombs made by Lingg. Schaack concluded, on the basis of interviews, that the anarchists had been experimenting for years with dynamite and other explosives, refining the design of their bombs before coming up with the effective one used at the Haymarket.

•Finally all eight defendants were adjudged guilty. Before being sentenced, Neebe told the court that Schaack’s officers were among the city’s worst gangs, ransacking houses and stealing money and watches. Schaack laughed and Neebe retorted, “You need not laugh about it, Captain Schaack. You are one of them. You are an anarchist, as you understand it. You are all anarchists, in this sense of the word, I must say.” Judge Gary sentenced seven of the defendants to death by hanging and Neebe to 15 years in prison.

•The sentencing of the defendants provoked outrage from labor and workers’ movements and their

supporters, resulting in protests around the world, and elevating the defendants to the status of martyrs, especially abroad. On the other hand, portrayals of the anarchists as bloodthirsty foreign fanatics in the press inspired widespread public fear and revulsion against the strikers and general anti-immigrant feeling, polarizing public opinion.

•The case was appealed in 1887 to the Supreme Court of Illinois, then to the United States Supreme Court where the defendants were represented by John Randolph Tucker, Roger Atkinson Pryor, General Benjamin F. Butler, and William P. Black. The petition for certiorari (Latin word, most commonly used in the US Supreme Court. means a writ or order of a higher court to send all documents in a case of it so that the higher court can review the lower court’s decision) was denied.

•After the appeals had been exhausted, Illinois Governor Richard James Oglesby commuted Fielden’s and Schwab’s sentences to life in prison on November 10, 1887. On the eve of his scheduled execution, Lingg committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled blasting cap which he reportedly held in his mouth like a cigar (the blast blew off half his face and he survived in agony for six hours).

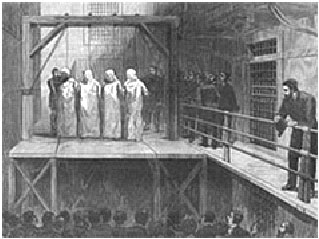

•The next day (November 11, 1887) four defendants—Engel, Fischer, Parsons, and Spies—were taken to the gallows in white robes and hoods. They sang the Marseillaise, then the anthem of the

international revolutionary movement. Family members including Lucy Parsons, who attempted to see them for the last time, were arrested and searched for bombs (none were found). According to witnesses, in the moments before the men were hanged, Spies shouted, “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.” In their last words, the men reportedly praised anarchism. Parsons tried to request to speak, but he was cut off when the signal was given to open the trap door. Witnesses reported that the condemned men did not die immediately when they dropped, but strangled to death slowly, a sight which left the spectators visibly shaken.

•Which is interesting in this case no actual bomber was ever brought to trial.

•Among supporters of the labor movement in the United States and abroad, the trial was widely believed to have been unfair, and even a serious miscarriage of justice. Prominent people such as novelist William Dean Howells, celebrated attorney Clarence Darrow, poet, and playwright Oscar Wilde and playwright George Bernard Shaw strongly condemned it.

•On June 26, 1893, John Peter Altgeld, the progressive governor of Illinois, himself a German immigrant, signed pardons for Fielden, Neebe, and Schwab, calling them victims of “hysteria, packed juries, and a biased judge” and noting that the state “has never discovered who it was that threw the bomb which killed the policeman, and the evidence does not show any connection whatsoever between the defendants and the man who threw it.” Altgeld also faulted the city of Chicago for failing to hold Pinkerton guards responsible for the repeated use of lethal violence against striking workers. Altgeld’s actions concerning labor were used to defeat his reelection.

•A statue dedicated to the policemen who died as a result of the violence at Haymarket Square was dedicated at the site of the riot in 1889. A monument to the men convicted in connection to the riot was erected in 1893 at the Forest Park, Illinois, the cemetery where they are buried.

•The Haymarket affair was a setback for the American labor movement and its fight for the eight-hour day. Yet it also can be seen as strengthening its resistance, especially in Chicago, where trade union activities continued to show signs of growth and vitality, culminating later in 1886 with the establishment of the Labor Party of Chicago.

•In 1889, the first congress of the Second International, meeting in Paris for the centennial of the French Revolution and the Exposition Universelle (A world’s fair held in Paris, France, from 6 May to 31 October 1889, an event considered symbolic of the beginning of the French Revolution.), following a proposal by Raymond Lavigne, called for international demonstrations on the 1890 anniversary of the Chicago protests. May Day was formally recognized as an annual event at the International’s second congress in 1891. The red flag was here created as the symbol that would always remind masses of the blood that the working-class has bleed, and continues to bleed, under the oppressive reign of capitalism.

•In 1904, the International Socialist Conference meeting in Amsterdam called on “all Social Democratic Party organizations and trade unions of all countries to demonstrate energetically on May First for the legal establishment of the 8-hour day, for the class demands of the proletariat, and for universal peace.” The congress made it “mandatory upon the proletarian organizations of all countries to stop work on May 1, wherever it is possible without injury to the workers.”

•An interesting feature is, though May 1 is now celebrated as International Workers’ Day, which is popularly known as May Day, in many countries across the world, in the US it is not celebrated. In the US and its neighboring country Canada, however, the official holiday for workers is Labor Day in September. This day was promoted by the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor, who organized the first parade in New York City. After the Haymarket Massacre, US President Grover Cleveland feared that commemorating Labor Day on May 1 could become an opportunity to commemorate the ‘‘riot’’s. Thus he moved in 1887 to support the Labor Day that the Knights supported. The official May 1 holiday in the US being observed as Loyalty Day.

•In the United States, efforts to officially switch Labor Day to the international date of May 1 have not been successful. In 1921, following the Russian Revolution of 1917, May 1 was promoted as “Americanization Day” by the Veterans of Foreign Wars and other groups as a counter to communists. It became an annual event, sometimes featuring large rallies. In 1949, Americanization Day was renamed to Loyalty Day. In 1958, the U.S. Congress declared Loyalty Day, the U.S. recognition of May 1, a national holiday; that same year, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower proclaimed May 1 Law Day as well.

•Some unions and union locals in the United States — especially in urban areas with strong support for organized labor — have attempted to maintain a connection with more left-wing labor traditions through their own unofficial observances on May 1. Some of the largest examples of this occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930s when thousands of workers marched in May Day parades in New York’s Union Square. Smaller far-left groups have also tried to keep the May Day tradition alive with more radical demonstrations in such cities as New York and Seattle, without major union backing.

•In 2006, May 1 was chosen by mostly Latino immigrant groups in the United States as the day for the Great American Boycott, a general strike of undocumented immigrant workers and supporters to protest H.R. 4437, immigration reform legislation which they felt was draconian. From April 10 to May 1 of that year, millions of immigrant families in the U.S. called for immigrants' rights, workers' rights, and amnesty for undocumented workers. They were joined by socialist and other leftist organizations on May 1.

•In 2007, May 1 was observed organizing a mostly peaceful demonstration in Los Angeles in support of undocumented immigrant workers ended with a widely televised dispersal by police officers.

•In March 2008, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union announced that dockworkers will move no cargo at any West Coast ports on May 1, 2008, as a protest against the continuation of the Iraq War and the diversion of resources from domestic needs.

•For May Day 2010, marches were being planned in many cities uniting immigrant and native workers including New York, San Francisco, Boston, Albany, Chicago, and Los Angeles — most of whom protested against the Arizona Senate Bill 1070.

•Members of ‘Occupy Wall Street’ held protests in a number of cities in Canada and the United States on May 1, 2012, to commemorate May Day.

•Though the US, where May Day originated, has not still recognized May 1 as Labour Day, but in

many a country of the world, the workers sought to make May Day an official holiday, and their efforts largely succeeded. May Day has long been a focal point for demonstrations by various socialist, communist and anarchist groups. In some circles, bonfires are lit in commemoration of the Haymarket martyrs, usually at dawn. May Day has been an important official holiday in countries such as the People’s Republic of China, North Korea, Cuba, and the former Soviet Union.

Mayday

Western Labor Parades

First Published: New York Times, May 2 1886, p. 2;

Source: http://womhist.binghamton.edu/iwd/doc2.htm;

HTML: for marxists.org in April, 2002;

Proofed and Corrected: by Dawn Gaitis, 2007.

Introduction

On May 1, 1886, working men mobilized in support of the eight-hour workday in cities across the United States. In this document, the New York Times reported on the diverse ways that the event unfolded across the United States, with some employers insisting that they would not pay a full day's wages for eight hours' work. One consistent theme, however, was the overwhelmingly male composition of the demonstrators.

WESTERN LABOR PARADES.

THE EIGHT-HOUR MOVEMENT IN CHICAGO.

STRIKERS MARCH THROUGH THE STREETS AND LISTEN TO HARANGUES, BUT NO VIOLENCE ATTEMPTED.

CHICAGO, May 1. – One good-sized procession, one small one, two small meetings, some gatherings too feeble to be called meetings, and less than 30,000 laboring men taking a holiday, either willingly or unwillingly, represent the first day of the era in which, it has been declared, eight hours shall constitute a day's work and 10 hours' pay shall be gotten for eight hours' work. The red flag has bobbed up here and there, some incendiary speeches have been made, and on one occasion the police have had to expel a crowd of 1,000 men in which the tramp outnumbered the workmen from railroad property. No blood has been spilled, and the 1st of May has been more of a holiday than it usually is in a land where people get up and move upon that date. The opinion is divided to-night as to whether this is all there is to be of the eight-hour movement or whether it is a parade prior to actual engagement. By far the most interesting part of today's features has been furnished by the freight handlers, for they were the men who came into mild conflict with the police. The men held a meeting on the Harrison-street Viaduct early this morning. The speeches were good-natured but firm, and there was nothing to show that the men had changed their minds about not going to work till they were given eight hours' work and ten hours' pay. After the meeting adjourned the strikers made a tour of the railroad freight depots. Wherever men were found at work they were induced, either by arguments or threats, to quit. At the Lake Shore station, the doors and windows were closed, but a striker with a sharp eye discovered that freight handlers were at work inside. The doors were broken down and a crowd 1,000 strong forced its way into the building. A couple of policemen tried to drive the intruders out, but, of course, could not. Capt. Buckley and a squad of men had better luck, and the crowd tumbled out into the street.

At the Wabash station, a notice to the effect that the road was in the hands of a Receiver and therefore could not be safely interfered with [h]ad no terrors for the crowd. The Illinois Central and Northwestern (Galena Division) freight handlers were visited but not molested because they have made their demands and given the railroad companies until Monday to answer. The freight handlers on every road running into Chicago, except the two last-named, are, therefore, on a strike, and declare that they will not return to work till their demands are granted. The railroad companies say they can not and will not grant the demands, and that the place of every freight handler who does not report for work Monday morning will be filled by a new man as soon as a man can be found. The companies say they will have no trouble in engaging new men.

The Mayor says he will furnish the new hands with protection. Many of the roads expect that the old men will return to work Monday morning.

About 10,000 Bohemians, Poles, and Germans employed in and about the lumber yards marched through the streets to-day with music and flags. There were two red flags carried at the head of the procession. At one point the procession and a funeral party came together at right angles, and there was a heated discussion as to which should have the right of way. The funeral lost. The procession rolled through the streets like a wave following a tugboat up a narrow stream. Both margins of the rush lapped into the fringing saloon, lapped them dry, and rushed out again, running a little slower for the detention. Some incendiary speeches advising that the torch be applied to the lumber yards were made. The other procession included 1,200 furniture men and woodworkers, who were quiet and orderly. The freight handlers held the second meeting in the afternoon and listened to more speeches.

As nearly as can be estimated the men not at work to-day were divided as follows: Laboring men taking a holiday of their own accord (including the 10,000 lumbermen), 15,000; freight handlers who have struck, 2,500; carpenters, woodworkers, and other workmen who have struck, 5,000; men who are practically locked out, their employers having closed their shops indefinitely because of the existing troubles, 5,000; total, 27,500. This estimate is probably an outside one.

The temper of the crowds who watched the processions marching through the streets to-day was that of curious interest only. Here and there a bit of sullenness was apparent, and this in the eyes of some indicated probable trouble as soon as another working week begins. An amusing feature of the strike for a shorter day came out today in connection with the demands of the men employed in the breweries, who demanded 10 hours' work, 10 percent. advance in wages, and free beer when they felt disposed to drink. The employers replied, granting an hour's less work per day without reduction of pay, and beer at 6, 9, 11, 12, and 4 o'clock, not more than three glasses to drink, however, at one time.

FEWER HOURS DEMANDED

ST. LOUIS, MO., May 1. – The furniture manufacturers of this city formed an association last night and unanimously resolved to operate their factories on the eight hours per day system after to-day, on a basis of eight hours' wages. They also resolved that they would tolerate no interference as to whom they shall employ or how their business shall be managed. An Executive Committee of seven was appointed, which will be submitted for settlement of all differences which may arise. In case of failure to settle any serious trouble, a general shut-down of the factories may at any time be ordered.

All the plumbers in the city, 200 in number, quit work this morning. They made a demand yesterday of the bosses that they adopt the eight-hour system without decreasing their wages, beginning today. The employers considered it too short a notice and asked for further time to consider the matter, requesting the men to remain at work until they should have arrived at a decision. This the men refused to do and stopped work.

Several hundred carpenters attended a meeting of the Carpenters' Union last night to consider the eight-hour movement. It was decided that beginning to-day they should go to work at 8 o'clock in the morning, take an hour for dinner, and quit at 5 o'clock in the afternoon, thus being in service eight hours. No strike is expected to grow out of this action, as the bosses have agreed to the proposition and the men demand to pay for but eight hours' work.

Two hundred men employed on the waterworks in East St. Louis struck to-day for eight hours' work per day and ten hours' wages. The city refused to grant their demand and will endeavor to procure new men to fill the strikers' places.

INDIANAPOLIS, Ind., May 1. – May Day has brought no general strike here among the workingmen, yet there is much unrest, and it cannot be definitely determined what will be done next week. Inquiry among the employers of the Sarven Wheel Works, which yesterday shut down until Wednesday, notifying their employes that they would give eight hours' pay for eight hours' work and that all who wished to comply with those terms could return to work on Wednesday, discloses a general feeling of hope that nothing precipitating trouble or protracted idleness will result out of the present condition of things. In some of the departments' requests for an increase in wages have been made and a few employers have evinced a desire to bring about a general demand for an increase in wages to the amount of from 10 to 15 percent. and the inauguration of the eight-hour rule. This does not seem to be generally supported. "Men can't step out on the street now and find bosses asking them to take jobs," said one of the Sarven wheel employes to-day. "We get from $1.25 to $1.50 per day as day men, spoke turners make $8 and $10 a week. These are not high wages, but they are as high as can be paid, probably, in the present condition of things." It seems likely that quite 90 percent. of the men will return to work next Monday unless the situation changes materially in the meantime. Employes say that a majority of the men would vote for 10 hours' work per day, as the firm had announced that wages would be regulated by the number of hours of work. Among the requests preferred by the men of the company was one for 10 percent. advance asked by the spoke assorted. These hope to meet with a favorable reply, but make no threats in case of refusal.

All of the employees of the Central Chair Company, 80 in number, went out on a strike this morning soon after the whistle blew. Last night a committee waited on the officers and asked for Saturday half-holidays without a decrease of wages. The firm was unable to grant the request and the men returned to work this morning apparently satisfied, but at a given moment retired in a body from the factory. They asked 57 hours' work for a week with 60 hours' pay, a concession granted in another chair shop. The men say they were not ordered out by the Knights of Labor, but came out on their own hook. The officers say the demand cannot be granted, which is in effect an increase of 5 percent. in pay. After paying all obligations last year the company had a surplus of 4 1/2 percent. To grant an increase of 5 percent. in wages would virtually lead to bankruptcy. If the price of chairs should be advanced wages could be increased, but otherwise, a general advance is impossible.

DETROIT, May 1. – The threatened strike at Grand Rapids is finally averted, and to-day is given up to a holiday there. The employers accept eight hours as a day's work with a corresponding reduction in wages on all workmen above $1 per day. On this basis, an advance of 5 percent is made, with the promise of as much more in two months. No question is raised over the employers' announcement that they will run their factories in their own way, employing and discharging whom they please. These matters are expected to adjust themselves.

There has been no difficulty in this city except in the breweries. Nearly all the workmen in these establishments are out for a reduction of hours, an increase of wages, and the enforcement of strict union rules. The builders and carpenters have compromised their difficulties by agreeing for a year on a basis of nine hours' work for the present ten hours' pay, and six months' notice thereafter of any change.

MILWAUKEE, Wis., May 1. – All brewers and maltsters in the city struck to-day. Not less than 3,000 men are affected.

LOUISVILLE, Ky., May 1. – In response to a demand for the adoption of the eight-hour system the Furniture Exchange to-day decided to shut down works unless employees would accept pay for eight hours' work.

WASHINGTON, May 1. – The eight-hour rule adopted by the various building trades unions will go into effect in this city Monday morning, and as most of the master builders and contractors are determined to resist the demand for shorter hours, building operations will be practically suspended until some compromise can be effected.

PITTSBURG[sic], Penn., May 1 – The furniture manufacturers have refused to grant their employees their demands for a reduction from ten to eight hours' labor per day, a general strike was inaugurated today. Nearly every furniture factory in Pittsburg and Allegheny City is closed and over 600 men are idle. Both sides are firm and there is no immediate prospect of a settlement.

The stonecutters in the two cities are also out for nine hours a day but will return to work on Monday, the employers generally having conceded to the demands. The carpenters will strike on Monday.

PHILADELPHIA, May 1. – The cabinetmakers refuse to compromise with the manufacturers, and a general strike will probably result. They demand that on and after May 8 eight hours shall constitute a day's work. The employees of the Hae & Kilburn Manufacturing Company were notified today that the demands would not be granted, and accordingly, 30 of the 50 cabinetmakers employed by the company laid down their tools and ceased work. The rest refused to join in the strike. The company employs about 200 men, Mr. C. Kilburn, the President of the company, said today that he will fill the places of the strikers next week.

TROY, N.Y., May 1. – This morning about 300 Italians, employed by the Delaware and Hudson Company in building a double track between Coon's Crossing and Ballston, struck for an increase of wages. They have been receiving $1.10 per day, demanded $1.25, and were offered $1.15, which they refused to accept. After stopping work they tied red handkerchiefs to their pickaxes and shovels and marched down the track in a body to another place where a second gang was at work and induced them to join the strikers. A large number of Italians arrived from New York by boat this morning and proceeded to Round Lake to work on the railroad.

HARTFORD, Conn., May 1. – At noon to-day two of the striking gasmen returned to work for $12 a week, including Sundays. They struck for $14 and the keeping open of a door to the retort room so that they could enjoy a draught of air. This opening cooled the retort, and Superintendent Harbison ordered the door closed, which order not being obeyed was enforced, first by the nailing up of the door and afterward by the bricking up of the aperture. The men, who had been getting $11 a week, then struck, but the Knights of Labor did not endorse them, and they had a hard time of it. All but the two names are still out, but it is expected that they will return by Monday. A meeting of all the labor organizations is called for next Thursday night to arrange for the employment of the unemployed persons in the building trades. It is supposed that the movement will be in the nature of a co-operative enterprise to put up small homes. Carpenters have been warned not to go to Bridgeport, as there is to be a labor movement there soon.

NEW-HAVEN, Conn., May 1. – Some of the dock laborers employed by the New-Haven and Northampton Railroad Company struck to-day for an increase from $1.35 to $1.50 a day.BOSTON, Mass., May 1. – In this city, the Trades Union of Carpenters, the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners, and the Plumbers' Union – 5,000 men in all – have resolved to demand eight hours on Monday and will strike if the demand is refused. The Master Builders' Association, 200 strong, unanimously adopted a manifesto yesterday afternoon bitterly condemning the action of the workmen, laying the whole blame on the labor unions, and declaring that the demands cannot be complied with without disaster to the business and working men both and that they will close up a business rather than submit to any interference.

PORTLAND, Me., May 1. – All cigarmakers belonging to the union here are out, the manufacturers have refused to grant their demand for an advance in wages.

Rosa Luxemburg

What Are the Origins of May Day?

Written: 1894. First published in Polish in Sprawa Robotnicza.

Published: From Selected Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg, tr. Dick Howard, Monthly Review Press, 1971, pp. 315-16.

Online Version: marxists.org April 2002.

Proofed: by Matthew Grant.

The happy idea of using a proletarian holiday celebration as a means to attain the eight-hour day was first born in Australia. The workers there decided in 1856 to organize a day of complete stoppage together with meetings and entertainment as a demonstration in favor of the eight-hour day. The day of this celebration was to be April 21. At first, the Australian workers intended this only for the year 1856. But this first celebration had such a strong effect on the proletarian masses of Australia, enlivening them and leading to new agitation, that it was decided to repeat the celebration every year.

In fact, what could give the workers greater courage and faith in their own strength than a mass work stoppage which they had decided themselves? What could give more courage to the eternal slaves of the factories and the workshops than the mustering of their own troops? Thus, the idea of a proletarian celebration was quickly accepted and, from Australia, began to spread to other countries until finally, it had conquered the whole proletarian world.

The first to follow the example of the Australian workers were the Americans. In 1886 they decided that May 1 should be the day of a universal work stoppage. On this day 200,000 of them left their work and demanded the eight-hour day. Later, police and legal harassment prevented the workers for many years from repeating this [size] demonstration. However, in 1888 they renewed their decision and decided that the next celebration would be May 1, 1890.

In the meanwhile, the workers’ movement in Europe had grown strong and animated. The most powerful expression of this movement occurred at the International Workers’ Congress in 1889. At this Congress, attended by four hundred delegates, it was decided that the eight-hour day must be the first demand. Whereupon the delegate of the French unions, the worker Lavigne from Bordeaux, moved that this demand be expressed in all countries through a universal work stoppage. The delegate of the American workers called attention to the decision of his comrades to strike on May 1, 1890, and the Congress decided on this date for the universal proletarian celebration.

In this case, as thirty years before in Australia, the workers really thought only of a one-time demonstration. Congress decided that the workers of all lands would demonstrate together for the eight-hour day on May 1, 1890. No one spoke of a repetition of the holiday for the next years. Naturally, no one could predict the lightning-like way in which this idea would succeed and how quickly it would be adopted by the working classes. However, it was enough to celebrate the May Day simply one time in order that everyone understands and feels that May Day must be a yearly and continuing institution [...].

The first of May demanded the introduction of the eight-hour day. But even after this goal was reached, May Day was not given up. As long as the struggle of the workers against the bourgeoisie and the ruling class continues, as long as all demands are not met, May Day will be the yearly expression of these demands. And, when better day’s dawn, when the working class of the world has won its deliverance then too humanity will probably celebrate May Day in honor of the bitter struggles and the many sufferings of the past.

1855: August 18. Sydney stonemasons win 8-hour day, (6-day week) followed by Melbourne stonemasons on 21 April 1856.

1856: Workers in Australia decided in 1856 to organize a day of complete stoppage together with meetings and entertainment in support of the Eight Hour Day. The day was so popular and had such strong support that it was decided to repeat the celebration every year.

The History of May Day

Published: International Pamphlets, 1932;

HTML: for marxists.org in March, 2002;

Proofed and Corrected: by Dawen Gaitis 2007.

The Fight for the Shorter Workday

The origin of May Day is indissolubly bound up with the struggle for the shorter workday – a demand of major political significance for the working class. This struggle is manifest almost from the beginning of the factory system in the United States.

Although the demand for higher wages appears to be the most prevalent cause for the early strikes in this country, the question of shorter hours and the right to organize were always kept in the foreground when workers formulated their demands against the bosses and the government. As exploitation was becoming intensified and workers were feeling more and more the strain of inhumanly long working hours, the demand for an appreciable reduction of hours became more pronounced.

Already at the opening of the 19th-century workers in the United States made known their grievances against working from "sunrise to sunset," the then prevailing workday. Fourteen, sixteen, and even eighteen hours a day were not uncommon. During the conspiracy trial against the leaders of striking cordwainers in 1806, it was brought out that workers were employed as long as nineteen and twenty hours a day.

The twenties and thirties are replete with strikes for reduction of hours of work and definite demands for a 10-hour day were put forward in many industrial centers. The organization of what is considered as the first trade union in the world, the Mechanics' Union of Philadelphia, preceded by two years the one formed by workers in England, can be definitely ascribed to a strike of building trade workers in Philadelphia in 1827 for the 10-hour day. During the bakers' strike in New York in 1834, the Workingmen's Advocate reported that "journeymen employed in the loaf bread business have for years been suffering worse than Egyptian bondage. They have had to labor on an average of eighteen to twenty hours out of the twenty-four."

The demand in those localities for a 10-hour day soon grew into a movement, which, although impeded by the crisis of 1837, led the federal government under President Van Buren to decree the 10-hour day for all those employed on government work. The struggle for the universality of the 10-hour day, however, continued during the next decades. No sooner had this demand been secured in a number of industries than the workers began to raise the slogan for an 8-hour day. The feverish activity in organizing labor unions during the fifties gave this new demand an impetus which, however, was checked by the crisis of 1857. The demand was, however, won in a few well-organized trades before the crisis. That the movement for a shorter workday was not only peculiar to the United States but was prevalent wherever workers were exploited under the rising capitalist system, can be seen from the fact that even in faraway Australia the building trade workers raised the slogan "8 hours work, 8 hours recreation and 8 hours rest" and were successful in securing this demand in 1856.

Eight-Hour Movement Started in America

The 8-hour day movement which directly gave birth to May Day, must, however, be traced to the general movement initiated in the United States in 1884. However, a generation before a national labor organization, which at first gave great promise of developing into a militant organizing center of the American working class, took up the question of a shorter workday and proposed to organize a broad movement in its behalf. The first years of the Civil War, 1861-1862, saw the disappearance of the few national trade unions which had been formed just before the war began, especially the Molders' Union and the Machinists' and Blacksmiths' Union. The years immediately following, however, witnessed the unification on a national scale of a number of local labor organizations, and the urge for a national federation of all these unions became apparent. On August 20, 1866, there gathered in Baltimore delegates from three scores of trade unions who formed the National Labor Union. The movement for the national organization was led by William H. Sylvis, the leader of the reconstructed Molders' Union, who, although a young man, was the outstanding figure in the labor movement of those years. Sylvis was in correspondence with the leaders of the First International in London and helped to influence the National Labor Union to establish relations with the General Council of the International.

It was at the founding convention of the National Labor Union in 1866 that the following resolution was passed dealing with the shorter workday:

The first and great necessity of the present, to the free labor of this country from capitalist slavery, is the passing of a law by which 8 hours shall be the normal working day in all states in the American union. We are resolved to put forth all our strength until this glorious result is attained.The same convention voted for independent political action in connection with the securing of the legal enactment of the 8-hour day and the "election of men pledged to sustain and represent the interests of the industrial classes."

The program and policies of the early labor movement, although primitive and not always sound, were based, nevertheless, on healthy proletarian instinct and could have served as starting points for the development of a genuine revolutionary labor movement in this country were it not for the reformist misleaders and capitalist politicians who later infested the labor organizations and directed them in wrong channels. Thus 65 years ago, the national organization of American labor, the N. L. U., expressed itself against "capitalist slavery" and for independent political action.

Eight-hour leagues were formed as a result of the agitation of the National Labor Union; and through the political activity which the organization developed, several state governments adopted the 8-hour day on public work and the U. S. Congress enacted a similar law in 1868.

Sylvis continued to keep in touch with the International in London. Due to his influence as president of the organization, the National Labor Union voted at its convention in 1867 to cooperate with the international working-class movement and in 1869 it voted to accept the invitation of the General Council and send a delegate to the Basle Congress of the International. Unfortunately, Sylvis died just before the N. L. U. convention, and A. C. Cameron, the editor of the Workingmen's Advocate, published in Chicago, was sent as a delegate in his stead. In a special resolution, the General Council mourned the death of this promising young American labor leader. "The eyes of all were turned upon Sylvis, who, as a general of the proletarian army, had an experience of ten years, outside of his great abilities – and Sylvis is dead." The passing of Sylvis was one of the contributing causes of the decay which soon set in and led to the disappearance of the National Labor Union.

First International Adopts the Eight-Hour Day

The decision for the 8-hour day was made by the National Labor Union in August 1866. In September of the same year the Geneva Congress of the First International went on record for the same demand in the following words:

The legal limitation of the working day is a preliminary condition without which all further attempts at improvements and emancipation of the working class must prove abortive....Congress proposes 8 hours as the legal limit of the working day.Marx on the Eight-Hour Movement

In the chapter on "The Working Day" in the first volume of Capital, published in 1867, Marx calls attention to the inauguration of the 8-hour movement by the National Labor Union. In the passage, famous especially because it contains Marx's telling reference to the solidarity of class interests

between the Negro and white workers, he wrote:

In the United States of America, any sort of independent labor movement was paralyzed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the republic. Labor with white skin cannot emancipate itself where labor with black skin is branded. But out of the death of slavery, a new vigorous life sprang. The first fruit of the Civil War was an agitation for the 8-hour day – a movement that ran with express speed from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California.Marx calls attention to how almost simultaneously, in fact within two weeks of each other, a workers' convention meeting in Baltimore voted for the 8-hour day, and an international congress meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, adopted a similar decision. "Thus on both sides of the Atlantic did the working-class movement, a spontaneous outgrowth of the conditions of production," endorse the same movement of the limitation of hours of labor and concretize it in the demand for the 8-hour day.

That the decision of the Geneva Congress was prompted by the American decision can be seen from the following portion of the resolution: "As this limitation represents the general demand of the workers of the North-American United States, the Congress transforms this demand into the general platform of the workers of the whole world."

A similar influence of the American labor movement upon an international congress and on behalf of the same cause was exerted more profoundly 23 years later.

May Day Born in the United States

The First International ceased to exist as an international organization in 1872 when its headquarters were removed from London to New York, although it was not officially disbanded till 1876. It was at the first congress of the reconstituted International, later known as the Second International, held at Paris in 1889, that May First was set aside as a day upon which the workers of the world, organized in their political parties and trade unions, were to fight for the important political demand: the 8-hour day. The Paris decision was influenced by a decision made at Chicago five years earlier by delegates of a young American labor organization – the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the United States and Canada, later known under the abbreviated name, American Federation of Labor. At the Fourth Convention of this organization, October 7, 1884, the following resolution was passed:

Resolved by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions the United States and Canada, that eight hours shall constitute legal day's labor from May First, 1886, and that we recommend to labor organizations throughout their jurisdiction that they so direct their laws as to conform to this resolution by the time named.Although nothing was said in the resolution about the methods by which the Federation expected to establish the 8-hour day, it is self-evident that an organization which at that time commanded an adherence of not more than 50,000 members could not declare "that eight hours shall constitute a legal day's work" without putting up a fight for it in the shops, mills, and mines where its members were employed, and without attempting to draw into the struggle for the 8-hour day still larger numbers of workers. The provision in the resolution that the unions affiliated to the Federation "so direct their laws as to conform to this resolution" referred to the matter of paying strike benefits to their members who were expected to strike on May First, 1886, for the 8-hour day, and would probably have to stay out long enough to need assistance from the union. As this strike action was to be national in scope and involve all the affiliated organizations, the unions, according to their by-laws, had to secure the endorsement of the strike by their members, particularly since that would involve the expenditure of funds, etc. It must be remembered that the Federation, just as the A. F. of L. today, was organized on a voluntary, federation basis, and decisions of a national convention could be binding upon affiliated unions only if those unions endorsed these decisions.

Preparations for May Day Strike

Although the decade 1880-1890 was generally one of the most active in the development of the American industry and the extension of the home market, the year 1883-1885 experienced a depression which was a cyclical depression following the crisis of 1873. The movement for a shorter workday received added impetus from the unemployment and the great suffering which prevailed during that period, just as at the present time the demand for a 7-hour day is becoming a popular issue on account of the tremendous unemployment which American workers are experiencing.

The great strike struggles of 1877, in which tens of thousands of railroad and steelworkers militantly fought against the corporations and the government which sent troops to suppress the strikes, left an impress on the whole labor movement. It was the first great mass action of the American working class on a national scale and, although they were defeated by the combined forces of the State and capital, the American workers emerged from these struggles with a clearer understanding of their class position in society, a greater militancy, and heightened morale. It was in part an answer to the coal barons of Pennsylvania who, in their attempt to destroy the miners' organization in the anthracite region, railroaded ten militant miners (Molly Maguires) to the gallows in 1875.

The Federation, just organized, saw the possibility of utilizing the slogan of the 8-hour day as a rallying organization slogan among the great masses of workers who were outside of the Federation and the Knights of Labor, an older and then still growing organization. The Federation appealed to the Knights of Labor for support in the movement for the 8-hour day, realizing that only a general action involving all organized labor could make possible favorable results.

At the convention of the Federation in 1885, the resolution on the walk-out for May First of the following year was reiterated and several national unions took action to prepare for the struggle, among them particularly the Carpenters and Cigar Makers. The agitation for the May First action for the 8-hour day showed immediate results in the growth of membership of the existing unions. The Knights of Labor grew by leaps and bounds, reaching the apex of its growth in 1886. It is reported that the R. of L., which was better known than the Federation and was considered a fighting organization, increased its membership from 200,000 to nearly 700,000 during that period. The Federation, first to inaugurate the movement and definitely to set a date for the strike for the 8-hour day, also grew in numbers and particularly in prestige among the broad masses of the workers. As the day of the strike was approaching and it was becoming evident that the leadership of the K. of L., especially Terrence Powderly, were sabotaging the movement and even secretly advising its unions not to strike, the popularity of the Federation was still more enhanced. The rank and file of both organizations were enthusiastically preparing for the struggle. Eight-hour day leagues and associations sprang up in various cities and an elevated spirit of militancy was felt throughout the labor movement, which was infecting masses of unorganized workers.

The Strike Movement Spreads

The best way to learn the mood of the workers is to study the extent and seriousness of their struggles. The number of strikes during a given period is a good indicator of the fighting mood of the workers. The number of strikes between 1885 and 1886 as compared with previous years shows what a spirit of militancy was animating the labor movement. Not only were the workers preparing for action on May First, 1886, but in 1885 the number of strikes already showed an appreciable increase. During the years 1881-1884 the number of strikes and lockouts averaged less than 500, and on the average involved only about 150,000 workers a year. The strikes and lockouts in 1885 increased to about 700 and the number of workers involved jumped to 250,000. In 1886 the number of strikes more than doubled over 1885, attaining to as many as 1,572, with a proportional increase in the number of workers affected, now 600,000. How widespread the strike movement became in 1886 can be seen from the fact that while in 1885 there were only 2,467 establishments affected by strikes, the number involved in the following year had increased to 11,562. In spite of open sabotage by the leadership of the K. of L., it was estimated that over 500,000 workers were directly involved in strikes for the 8-hour day.

The striking center was Chicago, where the strike movement was most widespread, but many other cities were involved in the struggle on May First. New York, Baltimore, Washington, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and many other cities made a good showing in the walkout. The characteristic feature of the strike movement was that the unskilled and unorganized workers were drawn into the struggle, and that sympathetic strikes were quite prevalent during that period. A rebellious spirit was abroad in the land, and bourgeois historians speak of the "social war" and "hatred for capital" which was manifested during these strikes, and of the enthusiasm of the rank and file which pervaded the movement. It is estimated that about half of the number of workers who struck on May First was successful, and where they did not secure the 8-hour day, they succeeded in appreciably reducing the hours of labor.

The Chicago Strike and Haymarket

The May First strike was most aggressive in Chicago, which was at that time the center of a militant Left-wing labor movement. Although insufficiently clear politically on a number of the problems of the labor movement, it was nevertheless a fighting movement, always ready to call the workers to action, develop their fighting spirit and set as their goal not only the immediate improvement of their living and working conditions but the abolition of the capitalist system as well.

With the aid of the revolutionary labor groups, the strike in Chicago assumed the largest proportions. An 8-hour Association was formed long in advance of the strike to prepare for it. The Central Labor Union, composed of the Left-wing labor unions, gave full support to the 8-hour Association, which was a united front organization, including the unions affiliated to the Federation, the K. of L., and the Socialist Labor Party. On the Sunday before May First the Central Labor Union organized a mobilization demonstration which was attended by 25,000 workers.

On May First Chicago witnessed a great outpouring of workers, who laid down tools at the call of the organized labor movement of the city. It was the most effective demonstration of class solidarity yet experienced by the labor movement itself. The importance at that time of the demand – the 8-hour day – and the extent and character of the strike gave the movement significant political meaning. This significance was deepened by the developments of the next few days. The 8-hour movement, culminating in the strike on May First, 1886, forms by itself a glorious chapter in the fighting history of the American working class.

But revolutions have their counter-revolutions until the revolutionary class finally establishes its complete control. The victorious march of the Chicago workers was arrested by the then superior combined force of the employers and the capitalist state, determined to destroy the militant leaders, hoping thereby to deal a deadly blow to the entire labor movement of Chicago. The events of May 3 and 4, which led to what is known as the Haymarket Affair, were a direct outgrowth of the May First strike. The demonstration held on May 4 at Haymarket Square was called to protest against the brutal attack of the police upon a meeting of striking workers at the McCormick Reaper Works on May 3, where six workers were killed and many wounded. The meeting was peaceful and about to be adjourned when the police again launched an attack upon the assembled workers. A bomb was thrown into the crowd, killing a sergeant. A battle ensued with the result that seven policemen and four workers were dead. The blood bath at Haymarket Square, the railroading to the gallows of Parsons, Spies, Fischer, and Engel, and the imprisonment of the other militant Chicago leaders, was the counterrevolutionary answer of the Chicago bosses. It was the signal for action to the bosses all over the country. The second half of 1886 was marked by a concentrated offensive of the employers, determined to regain the position lost during the strike movement of 1885-1886.

One year after the hanging of the Chicago labor leaders, the Federation, now known as the American Federation of Labor, at its convention in St. Louis in 1888, voted to rejuvenate the movement for the 8-hour day. May First, which was already a tradition, having served two years before as the concentration point of the powerful movement of the workers based upon a political class issue, was again chosen as the day upon which to re-inaugurate the struggle for the 8-hour day. May First, 1890, was to witness a nation-wide strike for the shorter workday. At the convention in 1889, the leaders of the A. F. of L., headed by Samuel Gompers, succeeded in limiting the strike movement. It was decided that the Carpenters' Union, which was considered best prepared for the strike, should lead off with the strike, and if it proved successful, other unions were to fall in line.

In his autobiography Gompers tells how the A. F. of L. contributed to making May Day an international labor holiday: "As plans for the 8-hour movement developed, we were constantly realizing how we could widen our purpose. As the time of the meeting of the International Workingmen's Congress in Paris approached, it occurred to me that we could aid our movement by an expression of world-wide sympathy from that congress." Gompers, who had already exhibited all the attributes of reformism and opportunism which later came to full bloom in his class collaborationist policy, was ready to get the support of a movement among the workers, the influence of which he strongly combated.

May Day Becomes International

On July 14, 1889, the hundredth anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, there assembled in Paris leaders from organized revolutionary proletarian movements of many lands, to form once more an international organization of workers, patterned after the one formed 25 years earlier by their great teacher, Karl Marx. Those assembled at the foundation meeting of what was to become the Second International heard from the American delegates about the struggle in America for the 8-hour day during 1884-1886 and the recent rejuvenation of the movement. Inspired by the example of the American workers, the Paris Congress adopted the following resolution:

The Congress decides to organize a great international demonstration, so that in all countries and in all cities on one appointed day the toiling masses shall demand of the state authorities the legal reduction of the working day to eight hours, as well as the carrying out of other decisions of the Paris Congress. Since a similar demonstration has already been decided upon for May 1, 1890, by the American Federation of Labor at its Convention in St. Louis, December 1888, this day is accepted for the international demonstration. The workers of the various countries must organize this demonstration according to conditions prevailing in each country.The clause in the resolution which speaks of the organization of the demonstration with regard to the objective conditions prevailing in each country gave some parties, particularly the British movement, an opportunity to interpret the resolution as not mandatory upon all countries. Thus at the very formation of the Second International, there were parties who looked upon it as merely a consultative body, functioning only during Congresses for the exchange of information and opinions, but not as a centralized organization, a revolutionary world proletarian party, such as Marx had tried to make the First International a generation before. When Engels wrote to his friend Serge in 1874 before the First International was officially disbanded in America, "I think that the next International, formed after the teachings of Marx, will have become widely known during the next years, will be a purely Communist International," he did not foresee that at the very launching of the rejuvenated International there would be present reformist elements who viewed it as a voluntary federation of Socialist parties, independent of each other and each a law unto itself.

But May Day, 1890, was celebrated in many European countries, and in the United States, the Carpenters' Union and other building trades entered into a general strike for the 8-hour day. Despite the Exception Laws against the Socialists, workers in the various German industrial cities celebrated May Day, which was marked by fierce struggles with the police. Similarly in other European capitals demonstrations were held, although the authorities warned against them and the police tried to suppress them. In the United States, the Chicago and New York demonstrations were of particularly great significance. Many thousands paraded the streets in support of the 8-hour day demand, and the demonstrations were closed with great open-air mass meetings at central points.

At the next Congress, in Brussels, 1891, the International reiterated the original purpose of May First, to demand the 8-hour day, but added that it must serve also as a demonstration on behalf of the demands to improve working conditions and to ensure peace among the nations. The revised resolution particularly stressed the importance of the "class character of the May First demonstrations" for the 8-hour day and the other demands which would lead to the "deepening of the class struggle." The resolution also demanded that work be stopped "wherever possible." Although the reference to strikes on May First was only conditional, the International began to enlarge upon and concretize the purposes of the demonstrations. The British Laborites again showed their opportunism by refusing to accept even the conditional proposal for a strike on May First, and together with the German Social-Democrats voted to postpone the May Day demonstration to the Sunday following May First.

Engels on International May Day

In his preface to the fourth German edition of the Communist Manifesto, which he wrote on May 1, 1890, Engels, reviewing the history of the international proletarian organizations, calls attention to the significance of the first International May Day:

As I write these lines, the proletariat of Europe and America is holding a review of its forces; it is mobilized for the first time as One army, under One Bag, and fighting One immediate aim: an eight-hour working day, established by legal enactment.... The spectacle we are now witnessing will make the capitalists and landowners of all lands realize that today the proletarians of all lands are, in very truth, united. If only Marx were with me to see it with his own eyes!The significance of simultaneous international proletarian demonstrations was appealing more and more to the imagination and revolutionary instincts of the workers throughout the world, and every year witnessed greater masses participating in the demonstrations.

The response of the workers showed itself in the following addition to the May First resolution adopted at the next Congress of the International at Zurich in 1893: The demonstration on May First for the 8-hour day must serve at the same time as a demonstration of the determined will of the working class to destroy class distinctions through social change and thus enter on the road, the only road leading to peace for all peoples, to international peace.

Although the original draft of the resolution proposed to abolish class distinctions through "social revolution" and not through "social change," yet the resolution definitely elevated May First to a higher political level. It was to become a demonstration of power and the will of the proletariat to challenge the existing order, in addition to the demand for the 8-hour day.

Reformists Attempt to Cripple May Day

The reformist leaders of the various parties tried to devitalize the May First demonstrations by turning them into days of rest and recreation instead of days of struggle. This is why they always insisted on organizing the demonstrations on the Sunday nearest May First. On Sundays workers would not have to strike to stop work; they were not working anyway. To the reformist leaders, May Day was only an international labor holiday, a day of pageants, and games in the parks or outlying country. That the resolution of the Zurich Congress demanded that May Day should be a "demonstration of the determined will of the working class to destroy class distinctions," i.e., the demonstration of the will to fight for the destruction of the capitalist system of exploitation and wage slavery, did not trouble the reformists, since they did not consider themselves bound by the decisions of international congresses. International Socialist Congresses was to them but meetings for international friendship and good-will, like many other congresses that used to gather from time to time in various European capitals before the war. They did everything to discourage and thwart joint international action of the proletariat, and decisions of international congresses which did not conform with their ideas remained mere paper resolutions. Twenty years later the "socialism" and "internationalism" of these reformist leaders stood exposed in all their nakedness. In 1914 the International lay shattered because from its very birth it carried within it the seeds of its own destruction – the reformist misleaders of the working class.